Fostering Good Discussions

How do you foster good discussions in the classroom?

One of the greatest benefits of peers and administrators conducting classroom observations is the opportunity to reflect upon pedagogy. It affords colleagues the chance to come to shared understandings of what good teaching and learning look like. In our work with iWalkthrough Classroom Observation, one distinction that is particularly important is the difference between “posing questions” and “facilitating discussion.” Posing questions describes times that teachers and students are engaged in a back-and-forth discussion that involves teachers commenting, correcting, or posing additional questions following most students comments. Facilitating discussion, however, involves mostly student voices, with the teacher only interjecting occasionally to summarize, redirect, or spur more conversation among and between students.

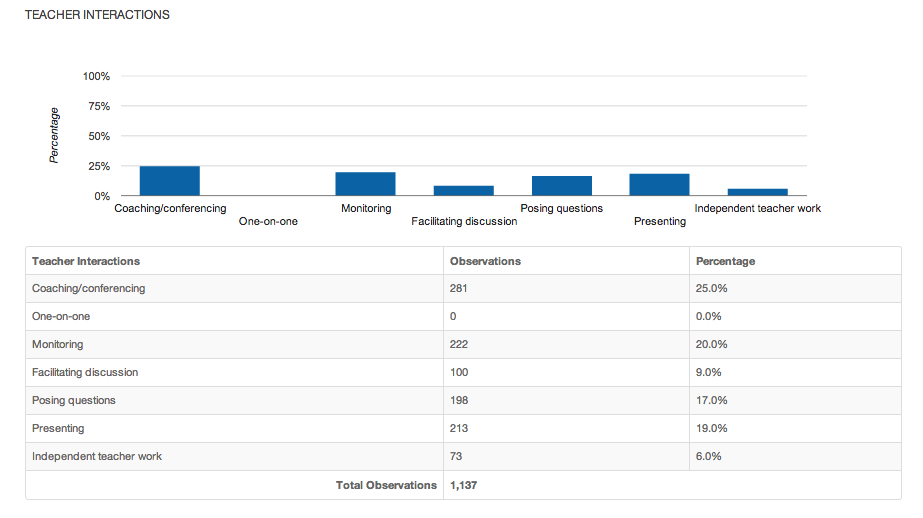

It’s not uncommon for a graph of Teacher Interactions to look something like this sample, combining several high schools using iWalkthrough Classroom Observation:

In this sample, teachers spend twice as much time presenting and monitoring as they do facilitating discussion. (One-on-one is an elementary school category, which is why there are no observations coded as one-one-one.) Posing questions are also almost twice as common. To be clear, it isn’t bad practice to monitor while students engage in group or individual work and it isn’t bad practice to present information. It is common, though, for teachers to ask about some strategies for improving classroom discussion. Here are 7 tips for having a student-led discussion in your classroom:

Preparing for Discussion

1. Decide whether your specific learning objective for the lesson actually lends itself well to a discussion. For example, if the expectation is that students have a clear understanding of the political and historical context and know the key figures associated with the start of first Gulf War, then presenting or having students read a text or perhaps view a video might help them reach this objective best. If, on the other hand, the learning outcome calls for students to examine the nature of modern day conflicts and compare and contrast them to past wars, then one viable way to accomplish this could via a whole class discussion.

2. Set up the classroom in a way where students can see one another. This is best accomplished by arranging chairs and desks in a circle or semi-circle. This sounds so basic, but it is often overlooked.

3. Establish a few ground rules or norms for the discussion. Examples include such expectations that only one person speaks at a time, the speaker will get our undivided attention, we will disagree in an agreeable way, ask questions to seek understanding, and all voices are important and should be heard.

Facilitating Discussion

4. Develop an essential question for the discussion and develop a series of follow-up prompts. Using the example above, an essential question could be ‘Based on our understanding of previous conflicts (e.g. WWI, Spanish-American War, etc.) was the first Gulf War inevitable?’ As the discussion begins, interject from time-to-time by digging deeper and asking follow-up questions like: can you give me a concrete example? Do you agree with what your fellow student just said? Was the first Gulf War the first of its kind and therefore the lessons of history just don’t apply? Why?’

5. Listen. A good facilitator has relinquished their control over the class and is sharing it with their students. A good rule of thumb for teachers who are trying to break their own habits of dominating a conversation is to take notes about the ideas you would like to share during the student-led discussion. Cross off the points that are made by students during the discussion. Those points that aren’t made should be, where possible, turned into questions.

6. Summarize. When involved in a good discussion, it can be hard to keep track of what the key points have been. In initial experiences, it’s helpful to have the teacher pause and summarize the discussion at five-ten minute intervals. Usually it helps to capture 3-4 key ideas that have been discussed and then to pose a question based on what students have been wrestling with.

7. Use structures. Discussion protocols or a formal structure can help students develop skills for interacting with one another and building on each others’ ideas. These protocols from the School Reform Initiative, are usually intended for faculty discussions, but many work well for students too. This video, from Teaching Channel, walks you through how to set up an effective Socratic Seminar, a formalized structure to promote student-to-student discussion:

After the Discussion

7. Debrief. For example, ask students to share one thing they learned from their classmates as a result of hearing their views and perspectives. Additionally, ask students to assess how well they adhered to the discussion norms, whether they helped, and whether the norms need to be clarified or modified in some way.

Classroom discussions can be a powerful and effective way to support your students’ achievement of a learning objective. When well prepared and facilitated it can also foster inquiry, perspective-taking, and community-building. If you have any other tips or suggestions you have used, we’d love to hear from you.